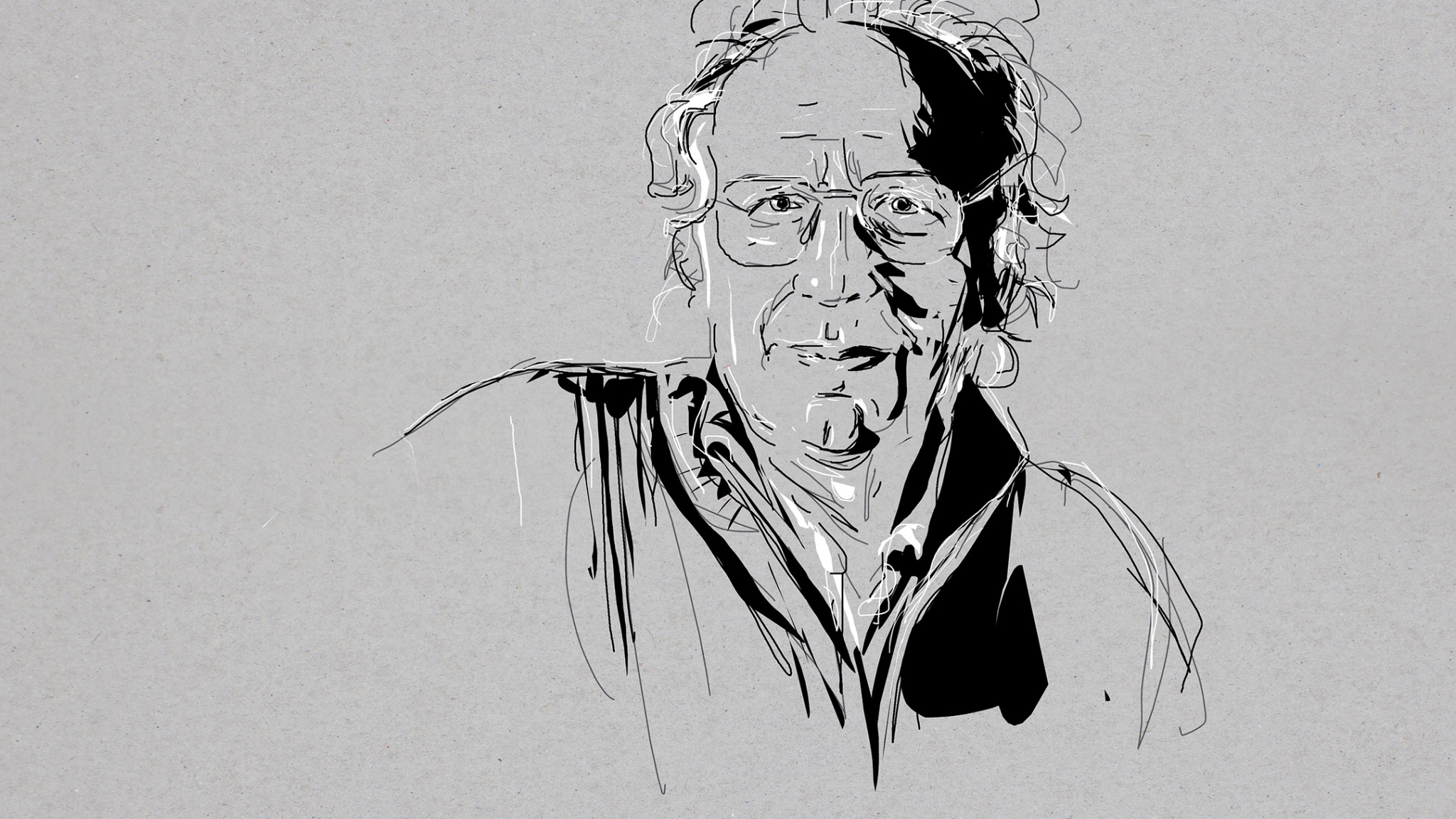

Daniel Hope on 'Music for a New Century' - An Interview with the Artist

Celebrating its 30th anniversary this season, New Century Chamber Orchestra has been resident in San Francisco’s Bay Area since its founding in 1992. One of just a handful of conductorless chamber orchestras in the world, the ensemble makes collaborative musical decisions, leading to an enhanced level of engagement from all involved. As well as giving masterful performances of the core chamber repertoire, New Century is known for reviving long-lost gems, experimenting with works from genres such as rock or jazz, and championing new music by commissioning, programming and premiering works by living composers.

Its commitment to contemporary music has grown even stronger under the leadership of Daniel Hope. The multifaceted artist and musical activist worked with New Century as Artistic Partner in the 2017–18 season, before being appointed Music Director, a role he took up at the start of the 2018–19 season. A shared passion for excellence, innovation and exploration has subsequently informed the performances and other projects both he and New Century have undertaken.

The latest of these is Music for a New Century, a stunning new recording for Deutsche Grammophon made as part of the ensemble’s 30th-anniversary celebrations. Recorded at Stanford University’s Bing Concert Hall, the album features four recent compositions, all commissioned or co‑commissioned by New Century.

Philip Glass’s Third Piano Concerto was given its US West Coast premiere by the ensemble in 2018, and is here performed by Ukrainian pianist Alexey Botvinov. The other three works are receiving their world premiere recordings: Mark‑Anthony Turnage’s Lament for solo violin and strings; Tan Dun’s Double Concerto for violin, piano, percussion and strings, for which Botvinov again joins Hope and New Century; and a brand-new composition by Jake Heggie, written especially to mark the ensemble’s anniversary year. Between them, these emotionally eloquent works span a striking breadth of musical ideas and styles; together, they encapsulate New Century’s advocacy of contemporary classical music.

Conductorless orchestras are rare creatures. The trend was set in Soviet Russia a century ago by Persimfans, the world’s first self-directed orchestra, and subsequently taken up by, among others, the Prague Chamber Orchestra, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and Amsterdam Sinfonietta. New Century itself has now been in existence for three decades. What drew you to working with the ensemble and what makes performing with its musicians so special?

From my very first encounter with the players, I was struck by their passion and joy for music, as well as their unrelenting wish to “dig deeper” inside the score. The energy that flies around the podium makes it a particularly inspiring and rewarding experience.

Can you tell us something about the working practices you’ve established with New Century? How does the dynamic function between you and the rest of the players?

New Century is certainly one of the most democratic ensembles I have worked with. Everything is up for discussion and this is refreshing. We bounce ideas off one other: in rehearsal often trying out extremes of tempi, articulation and phrasing. Then comes the moment when we have to focus on a group interpretation, a group sound. I’ve learned a great deal listening to and playing with the musicians, and I would venture to say I’ve offered them one or two surprises along the way!

In proportion to their considerable rarity, conductorless orchestras have played a supersized role in the promotion of new music. How important was contemporary music in your list of priorities when you took charge as Music Director?

It remains crucial. New Century has built a rich tradition of commissioning dozens of pieces in its 30‑year existence. When I began to work with the orchestra as Music Director, I was determined to grab that spirit and keep it alive. I was also keen to see if we could come up with an album of music which our organisation had been a part of creating.

The three works that are receiving their world premiere recordings on this album – the Turnage, Heggie and Tan Dun – were very much part of my agenda. The Philip Glass Piano Concerto, which is a superb piece, was first performed in Boston around the time of my appointment as Music Director. New Century gave its West Coast premiere the following year.

One might not automatically think of placing these four composers together. But by doing so, we’re celebrating the orchestra and its creative engagement with new music. I wanted pieces for the album that would encapsulate the essence of what New Century does. And it was a wonderful gesture by Deutsche Grammophon to support this album so wholeheartedly.

These pieces are clearly written in the distinctive language of each of their composers. And yet they appear to share a similar emotional directness. What do you think lies behind this?

Apart from the intentional pun in the album’s title, Music for a New Century, I feel there’s been a dramatic shift in contemporary music over the past ten years and that is also reflected in these compositions. Many composers seem to have returned to that old-fashioned concept known as “melody”! But what interests me even more is how certain composers have reinvented or reimagined melody, or perhaps come to terms with the way they define it in today’s world. Here we have four very different composers, two from the United States, one from China and one from Great Britain. And yet each one, in his own right, has conjured up his own unique approach to melody.

New Century was one of twelve North American ensembles to co-commission Philip Glass’s Piano Concerto No. 3. You’ve now recorded the work together, and with your friend Alexey Botvinov as soloist. Could you tell us something about the music?

I have long admired Philip Glass’s music, as well as performing it a great deal. Alexey Botvinov has too, he has a real affinity to it. I also wanted to continue our recorded collaboration after our Schnittke and Silvestrov albums for violin and piano. The Glass Concerto was, in a sense, inspired by the “soul” of JS Bach. And yet Glass explains that Bach’s music was not consciously in his mind as he composed this new work. It was rather Bach’s influence in a broader sense, which he describes as “unavoidable”. Glass came into close contact with Bach’s music during his studies with Nadia Boulanger: as a result, he feels there is a certain overlap within their musical spheres.

British composer Mark-Anthony Turnage is known for music that can be confrontational, with a visceral emotional quality. He notes that you are “a player with a lot of heart” and that he wanted to capture that in Lament. What led you to commission the piece?

I love both Mark’s music and his energy. We’ve known each other for years, and we both support Arsenal Football Club! Previously I had commissioned a Concerto for two violins and orchestra from him, for Vadim Repin and myself, entitled Shadow Walker. And several years before that, Mark wrote a piano trio for us when I was in the Beaux Arts Trio.

Mark called me after Shadow Walker with an idea for a piece, based on something he’d already sketched and wanted to orchestrate. Lament was written as a tribute to the partner of his publishing manager, as a way of coming to terms with his passing. Mark sent me the first draft of the violin part and it struck me immediately as being highly lyrical and expressive, which are not necessarily traits I would immediately associate with his music. This was different: deeply emotional, passionate, almost heart-on-sleeve.

I asked him to compose Lament as a piece that I could play/direct from the fiddle, really because I wanted to retain the initial chamber music element. Mark has scored it in a very clever way, so while it is complex and contains a high level of rhythmic detail, it works beautifully as a conductorless tone poem. It also fits New Century, which has been led from the first chair or by the solo violin since its inception.

We were able to make Lament a co-commission with Radio France, the NFM Leopoldinum Orchestra in Wrocław and Amsterdam Sinfonietta.

I gave the world premiere in February 2021 in Paris with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, behind closed doors due to the pandemic, but as a radio broadcast. New Century and I gave its first public performance and US premiere some months later. I’ve played it many times since, and each time I’m struck by the way in which its musical language is inspired by the past, and yet still adheres to Mark’s singularly present form of expression.

Although Mark was not with us in person, he was linked in to the studio in Paris during the first rehearsals, and again to us in San Francisco during the whole recording session, giving us advice and suggestions for the piece. I feel like we’ve grown the work together, even though we’ve not been in the same room.

The original plans for Tan Dun’s Double Concerto had to be altered because of the pandemic. It finally brought the orchestra together for the first time in over a year for its virtual world premiere at Bing Concert Hall. The score subverts the conventional three-movement concerto form with its constantly evolving contrasts of tempo and mood, yet it’s clearly a virtuoso showpiece for both the soloists and the two percussionists. How did this commission come about?

Tan Dun is a close friend and I’ve been privileged to know him now for 20 years. We’ve worked together on numerous occasions and I’ve also performed two of his violin concertos with him as conductor. Every time it’s an incredible exchange of both energy and ideas. He has such a clear way in which he hears and imagines his music. His grasp of rhythm and sound colours is second to none. He is also, like me, greatly inspired by music from other genres, be it folk, traditional or even rock. Just being in his “orbit” is tremendously exciting.

I asked Tan Dun if he might write a piece for New Century, knowing how busy he is and expecting to wait five or ten years for him to find the time to do it. But one night he called me: he really wanted to make it happen and suggested revisiting a triple concerto that he’d written for a large-scale orchestra and creating a new, dynamic version of it. The Double Concerto came out of that conversation and together with New Century it became a co-commission with Alexey Botvinov’s “Odessa Classics” Festival. We were even able to perform it in Odessa, a few months before the war. We are thrilled to have it.

Can you say something about the practicalities of performing a work that began life as a large-scale composition without a conductor?

We’d initially planned for Tan Dun to conduct his new piece with us. When that proved impossible, due to travel restrictions in China, I wasn’t initially sure if we could fully do justice to it without a conductor. He revised it a few times with this in mind, and finally we got a perfect fit. New Century’s tight-knit strings and superb percussionists were entirely on top of the piece. It works equally well with or without a conductor.

Since we gave the world premiere in May 2021, I’ve also performed it in Istanbul with Alexey Botvinov, but this time with Tan Dun conducting. At our first rehearsal he joked: “You don’t need me to conduct this now; you can do it perfectly without me!” But I insisted I wanted him to conduct, not least because I was curious to see how the piece might differ in this combination.

Watching the video of the Tan Dun premiere, it is clear how closely the players watch you and how intently you all listen to one another. It also helps that his Double Concerto and the other pieces on the album are clear in texture and precise in rhythm. Those are particular hallmarks of Jake Heggie’s writing. What is your connection to him, given that he’s best known as an opera composer?

Jake first contacted me about a piece he was writing inspired by “Violins of Hope”. That’s a project that restores instruments formerly owned by Jewish musicians before and during the Holocaust and brings them back to life with an international series of concerts. The exhibition was coming to San Francisco’s Bay Area in early 2020 and had commissioned Jake to write a song cycle that tells the story of a Holocaust survivor in song and through the voice of their violin.

Jake composed the piece for the mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke, myself and a string quartet which included New Century musicians. It was called Intonations: Songs from the Violins of Hope. I realised how powerful this story was and wanted to be involved, so I agreed to perform and record it. Jake and I have since struck up a friendship, and I invited him to join me for one of my Hope at Home episodes, some of which we filmed in San Francisco with New Century during lockdown.

Although Jake is arguably best known for his operas and vocal music, I subsequently commissioned him to write a new work for violin and piano in my role as President of the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn. His Fantasy 1803, which was inspired by Beethoven’s residency at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna in 1803, includes echoes of George Bridgetower, the fascinating British violinist of African descent to whom Beethoven first dedicated his so-called “Kreutzer” Sonata. Jake’s chamber piece is superb, with wonderfully taut melodic lines and a tonal, highly expressive language.

I was looking for a celebratory work to mark New Century’s 30th anniversary and to open our concerts during a major European tour in the summer of 2023. I felt that Jake, himself an institution in the musical life of San Francisco, would be the ideal person to ask. I also think that coupling his commission for New Century with the Philip Glass Piano Concerto gives a clear snapshot of how certain American music sounds in the 21st Century.

Have you seen the score of Heggie’s new work yet?

Yes, it only recently arrived and is called, appropriately, Overture. That moment of anticipation, the first time one receives the score of a new work, is entirely palpable. One used to unwrap a parcel, perhaps an envelope to examine a manuscript. Nowadays one simply clicks on a file. But the result is the same. A rush, a feeling of excitement. And then a longing to discover this joyful, celebratory work. Full of exuberance. After all, this is a celebration, is it not? Of music, for a new century…