Daniel Hope’s tribute to Alfred Schnittke

Daniel Hope’s new album ‘Schnittke – Works for Violin and Piano’ is set for international release on 5 February 2021 and was recorded with Ukrainian pianist Alexey Botvinov, an acclaimed interpreter of the composer’s works. The programme embraces everything from the immediately accessible Polka and Tango to the multi-layered Violin Sonata No.1, the work that first ignited Hope’s passion for Schnittke’s music.

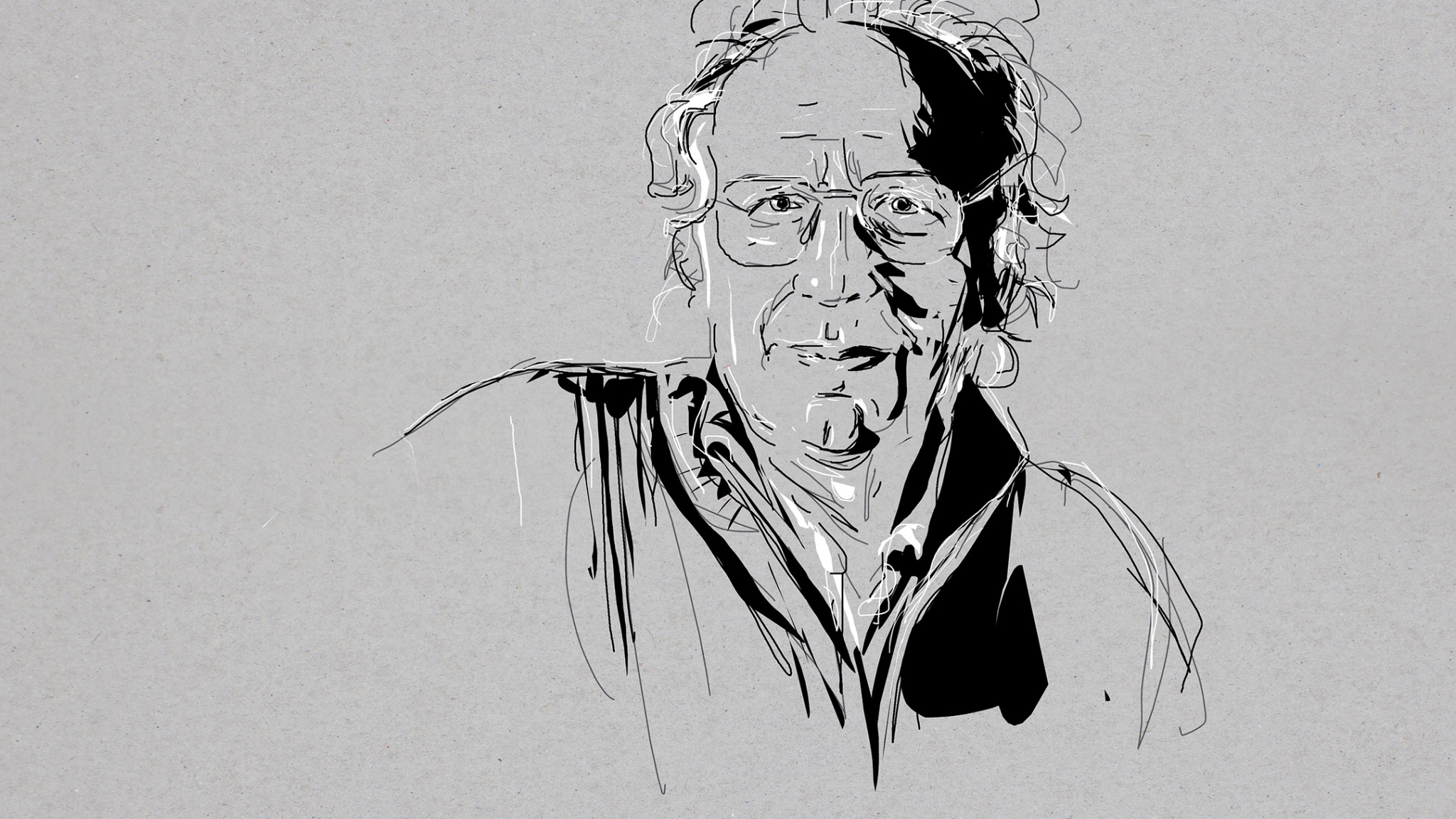

Daniel Hope was fifteen when he first encountered the music of Alfred Schnittke in 1989. The experience launched a love affair with the Russian composer’s work that has continued to deepen ever since. The violinist’s latest album pays homage to this maverick genius, whose elegant explorations of past styles and free-thinking experiments in “polystylism” were both original and iconoclastic, at times bringing him into conflict with the Soviet authorities.

The album opens with Suite in the Old Style, five transcriptions of pieces written in the Baroque fashion, originally for various film scores. It is followed by Polka, inspired by Gogol’s compelling short story “The Overcoat”, and Tango, written for Elem Klimov’s 1981 film Agony. These colourful pieces preface the First Violin Sonata (1963), now among the most frequently performed works for violin and piano of modern times.

Newcomers to Schnittke’s music are often surprised to discover the prominence given to the past in his compositions, sometimes subverted by the shock of the new, sometimes crafted in a style that Mozart might have recognised. Suite in the Old Style and Gratulationsrondo, a short work in honour of the violinist Rostislav Dubinsky, could easily pass for long-lost pieces from the eighteenth century.

“Although both hark back to the past and celebrate Schnittke’s love of ‘pastiche’, they are also a subjective reaction to the sounds of the early 1970s,” Daniel Hope explains. “His Suite in the Old Style reworks music from two of his film scores – Elem Klimov’s comedy Adventures of a Dentist and a spoof documentary about, of all things, sport. The original version of the Suite was for violin and harpsichord, an instrument which appears to have been in the air of Soviet music.”

Mieczysław Weinberg, the violinist adds, had scored a tremendous hit in 1969 with his music for the Russian cartoon version of Winnie-the-Pooh which, like Schnittke’s Suite, used the harpsichord in a neo-Baroque fashion. “Film music gave Schnittke a certain freedom to experiment with different idioms and to plant the seeds which would ultimately blossom into his concert works. He also admitted that by writing the Suite, he had fulfilled his wish ‘once to write completely naively’. But as always with Schnittke, there is more to it than meets the eye. And of the Gratulationsrondo he confessed to presenting us with ‘corpses wearing make-up’, a deeply unsettling notion.”

There was room in Alfred Schnittke’s art for great stylistic diversity and, increasingly in his later works, for contemplation of mankind’s spiritual nature. The latter vein informs one of the highlights of Daniel Hope’s album, the haunting Madrigal in memoriam Oleg Kagan for solo violin.

The composer’s well-developed sense of irony, meanwhile, surfaces in the First Violin Sonata and is also present in the album’s closing track, Stille Nacht (1978), an unnerving, spiky arrangement of a Christmas favourite that appears to suggest that the saccharine-sweet fiction of official propaganda was not matched by the grim reality of life under the Soviet régime.

“I feel that there must have been a naturally rebellious streak in him,” comments Daniel Hope, who got to know and work with Schnittke during a series of meetings and conversations in the early 1990s. “He certainly displayed a wicked sense of humour,” the violinist recalls. “He once famously described his First Symphony, a work I also performed and am still fascinated by, as ‘beginning like a circus and ending in an apocalyptic, terrifying way’. Here again we see the extremes in his character and, ultimately, in his music. The other quote of his which I love and can relate to is: ‘Good music cannot be created by good intentions.’”

Soon after Daniel Hope met Alfred Schnittke for the first time in 1992, he was invited to appear on a television show in Munich. Among his fellow guests was a former senior officer in the KGB with whom he shared a car ride to the airport after the programme finished. “I realised I had a unique, 40‑minute opportunity to ask him things without him being able to leave,” remembers Hope. “Much to his visible discomfort, I bombarded him with questions about Rostropovich, Solzhenitsyn, Shostakovich and Schnittke. He did his best to brush off any criticism as the mere histrionics of an 18-year-old upstart (which indeed I was), but when we got to Schnittke, he poured disdain on him. I’ll never forget what he said, sanctimoniously: ‘Young man, the others were legends, celebrated Soviet Artists. Schnittke was nothing but a punk’.”

The former KGB man’s dismissive attitude reflected received Soviet wisdom on a composer who drifted in and out of favour as cultural politics thawed, then chilled, then thawed again. Schnittke’s public reputation rested more on the sixty-six film scores he wrote for state film companies than on his works for the concert hall, many of which were routinely condemned in official publications. Daniel Hope recalls how he, unlike the composer’s Soviet critics, was immediately drawn to the ambivalence and stylistic diversity of the Violin Sonata No.1.

“The First Sonata is a work of extremes,” Hope observes, “and I think that was part of what fascinated me. Each movement is like an encapsulation of a musical ideal: the first is Schnittke’s own take on, and dislike of, serial music; the second revisits his obsession with folk music; the third brandishes a blatant quotation of Shostakovich’s Piano Trio; and the finale presents his amalgamation of the Latin American ‘La cucaracha’ theme with all of the previously gathered material. It’s exhilarating both to perform and to listen to: the first time I heard it, back in 1989, I was listening to twentieth-century music with somewhat unblemished ears. Perhaps that provoked me even more.”

Listen to the first pre-release track ‘Schnittke: Tango from the music to the film “Agony”’ now!