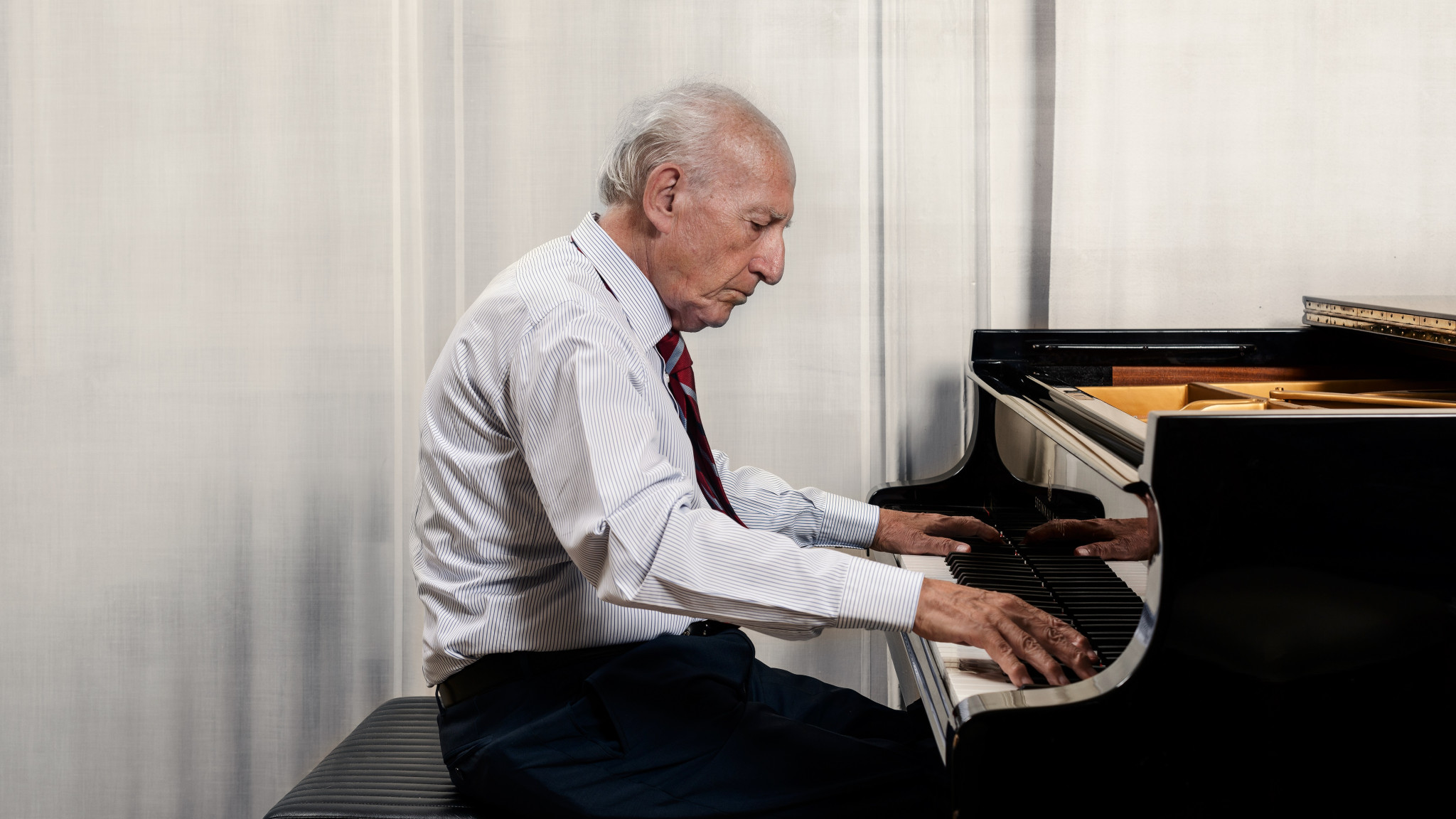

Music – A Higher Revelation

This latest recording from Maurizio Pollini features Beethoven’s final three piano sonatas, works he first recorded more than four decades ago. “The sonatas were published separately,” notes Pollini, “but can be seen as forming a unified cycle.” He goes on to say, “Having played these works many, many times in the last 40 years, I’ve continually discovered new riches in every detail. In these masterpieces we see Beethoven departing from conventional form – alongside sonata form we find variation and fugue both playing significant, even decisive roles, and we can also see completely free episodes which appear to be direct translations of the composer’s subjective feelings. I’m reminded of a phrase that Bettina Brentano (in a letter to Goethe) attributed to Beethoven: ‘Music is a higher revelation than any wisdom or philosophy.’”

In the Sonata in E major op. 109 (completed in September 1820) the first two movements – played without a break – function almost as an introduction to the much longer finale. There are traces of sonata form in the opening movement: the initial Vivace, ma non troppo includes a kind of development and recapitulation, but in place of a second subject we find an improvisatory, almost fantasia-like Adagio espressivo. Driven and concise, the Prestissimo is an agitated, stormy piece of writing, with taut, clear-cut lines. Here we can clearly discern bithematic sonata form, with the bass line of the first theme becoming the principal element of a canon during the brief development section.

New horizons are then opened up as the traditional finale is replaced by a variations movement. In his late works, Beethoven’s use of variations was structural in conception, bearing no relation to the virtuosic-ornamental type then in vogue. His main point of reference seems rather to have been Bach’s then very unfashionable Goldberg Variations. The hymn-like theme, with its intimate beauty, consists of two eight-bar phrases. Different aspects of the theme are reflected and reworked in the variations, the first transforming its melody, the second being notable for its unique breadth and variety of character. Variation III is written in double counterpoint, while the freer contrapuntal style of the fourth variation intensifies the cantabile nature of the theme. The fifth is a strict three-part fugue whose crisp energy forms an extraordinary contrast with the gentleness and luminous transfiguration of the sixth and last, itself seemingly a succession of variations united by the almost constant presence of a dominant pedal. This repeated B becomes a trill, moving from register to register: in the final section it shifts to the middle register, as the left hand plays rapid demisemiquaver patterns while in the upper register, above the trill, a shattered version of the theme appears in isolated staccato notes, sounding almost like pizzicato string playing. With this highly innovative use of sonorities, Beethoven seems – as so often in his late-period masterpieces – to lead the listener into ethereal and rarefied regions. To conclude the work, we hear one last presentation of the gentle, meditative theme.

The Sonata in A flat major op. 110 (1821) is lyrical and reflective in tone, and its free formal procedures display a notable subjectivity. Sonata form is there in the first movement, but reimagined in an entirely original manner. Take the presentation of the first theme, for example, which is divided into two phrases of four and seven bars respectively – its intense cantabile writing is thick with details later developed by the composer. The rapid demisemiquaver figurations that follow seem to suggest a free fantasia, but in fact serve as a transition to the second subject and have the same harmonic foundation as the opening bars (in the recapitulation they provide an accompaniment to the first subject). The lyrical arc of the second subject soars into the top registers of the keyboard; the brief development section is based on the first four bars alone.

A sudden change in mood is marked by the abruptness with which the Allegro molto in F minor (a scherzo and trio) bursts in. This movement is characterized by alternations in dynamics between forte and piano, a dramatic use of chiaroscuro, and allusions to popular songs, with a central section whose writing is impassioned, restless and disquieting.

The finale comprises an Adagio and a Fuga that together form a single block. The inwardlooking language of the Adagio suggests the idea that the piano is yearning to transcend its physical limitations and move into the realm of vocal music, resulting in some highly original sound effects: Beethoven’s ability to make his keyboard instrument “speak” culminates perhaps in the famous series of repeated A naturals that simulates the Bebung vibrato technique associated with the clavichord. The recitative section incorporating the Bebung passage is followed by the bleak desolation of the Arioso dolente (Klagender Gesang) [Song of lamentation], but out of the cadence in which the lament fades away there emerges the limpid, tranquil start of the fugue, which represents a desire to rediscover a rational, humanistic trust (it is radically different from the fugue of bewildering, unrestrained complexity that brings the “Hammerklavier” Sonata op. 106 to an end). The fugue is suddenly interrupted by a return to the Arioso: Perdendo le forze, dolente (Ermattet, klagend) [weary, lamenting], writes Beethoven, evoking a state of exhaustion which manifests itself in the fragmentation of the lament tune. When this ends, a repeated chord that continually grows in volume heralds a new sense of security; with its subject inverted, the fugue returns, now acquiring a somewhat unreal quality. In slightly inaccurate Italian, Beethoven here writes poi a poi di nuovo vivente (nach und nach wieder auflebend) [gradually coming to life again]: shedding its contrapuntal writing, the fugue builds to a jubilant conclusion.

Pollini observes, “The use of powerful contrasts is a constant in Beethoven’s music: the final movement of Op. 110 fluctuates between very different moods, while the deeper, more mysterious meaning of Op. 111 is to be found in the relationship between its tragic opening movement and the Arietta con variazioni.”

At the end of the slow, dark, tension-laden introduction (marked Maestoso) of the Sonata in C minor op. 111 (published in 1823), a trill in the lower register leads into the Allegro con brio ed appassionato and the arrival of the first subject. With its jagged linearity and stark, energetic concision, it provides a contrast with the sombre, compact chords of the introduction. The contrapuntal writing, almost fugato at times, adds to the tension of the first subject, which dominates the opening movement, the second subject injecting just a brief moment of intensely lyrical respite before being swept away by a variant of the first. The lyrical second subject does reappear in slightly expanded form in the recapitulation, then the coda fades away, pianissimo and in C major.

The relentless drama of the first movement is counterbalanced by the sublime, meditative quality of the Arietta con variazioni, which seems to lift the movement beyond any feelings of tragedy, despair or disillusionment and instead transform them with a visionary, spiritual idiom that precludes continuation or a return to other expressive dimensions. Anton Schindler expressed regret about the lack of a third movement, reporting that Beethoven had told him he had not had time to compose one, but this perhaps betrays his own lack of understanding of the Arietta. The composer takes a theme of pure simplicity as the starting point for a journey towards the ineffable. This begins with a regular succession of variations built on ever shorter note values, before exploring freer solutions that can no longer be traced back to specific conventional schemes. The theme starts to become less recognizable in the rhythmically complex third variation. The fourth is a double variation which opens out into a free-form episode in which the music lingers ecstatically on trills, creating moments of shimmering iridescence and taking the hands as far away from one another as possible. The fifth sees a varied repeat of the theme, which is then heard in the upper register, in an atmosphere of rarefied catharsis, preceded by and swathed in further ethereal trills.

In one of his conversation books, Beethoven wrote down and underlined some words from a famous passage by Kant (adding three admiring exclamation marks): “the moral law within us and the starry heavens above us”. While there is no way of proving a link between this and the fourth variation of the Arietta, Maurizio Pollini sees their possible connection as a fascinating hypothesis.

Paolo Petazzi