Maurizio Pollini Revisits Late Masterpieces by Beethoven

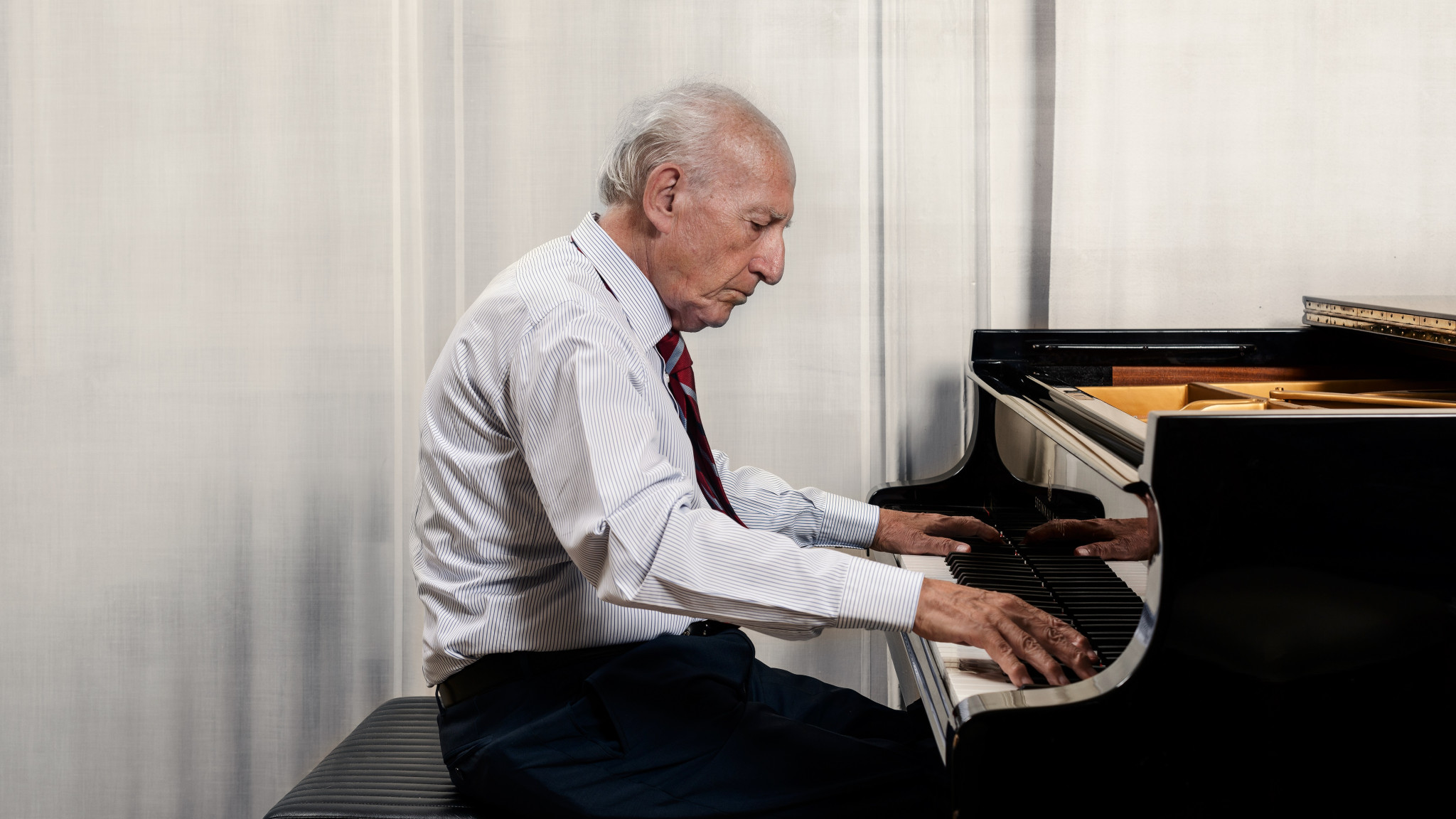

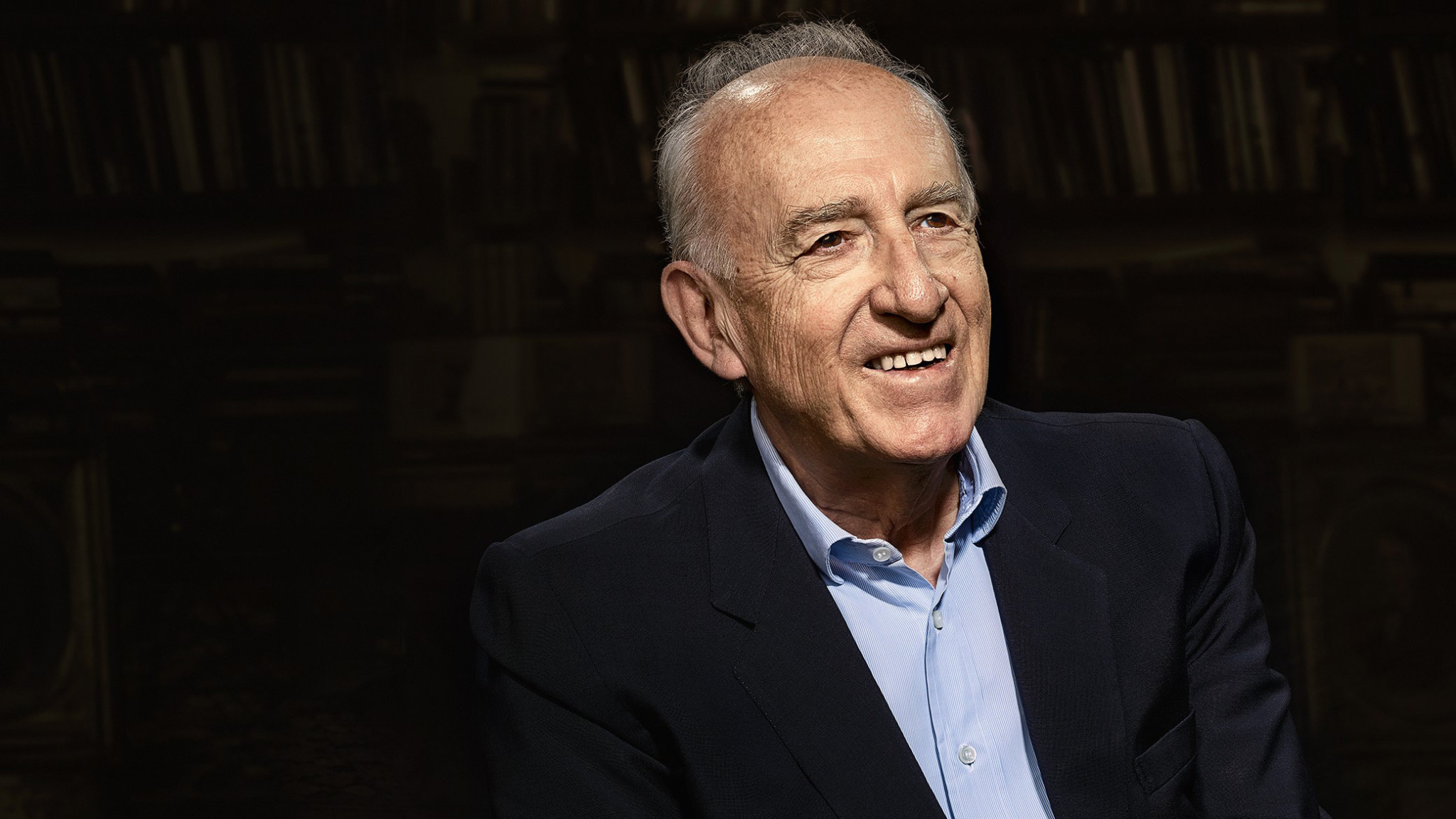

Beethoven – The Late Sonatas Opp. 101 & 106 marks the completion of Maurizio Pollini’s survey of the five late piano sonatas. His landmark 1970s recordings of these works were recognised at the time with a Gramophone Award. A few years ago the pianist decided to revisit the five sonatas, and in 2019 made an acclaimed second recording of the final three at the Herkulessaal in Munich. Now he has returned to the same hall to record Opp. 101 and 106 – among the most technically challenging and musical adventurous works in the concert repertoire. Deutsche Grammophon will release his new album on 2 December 2022.

The quixotic nature of Beethoven’s A major Sonata, Op. 101 and the complexities of the “Hammerklavier” Sonata, Op. 106 offer infinite scope for interpretation. “Every Beethoven piano sonata is a different world,” observes Maurizio Pollini. “He finds a different character in each one, from the first to the last. Each is unique.” The A major Sonata, he adds, “is very free”. Drafted in the summer of 1815 and completed the following year, its four movements are markedly different in style and substance from those of the composer’s earlier sonatas for piano. “It’s a great challenge to understand and play it,” says Pollini.

The scale of the challenge, however, pales beside that set by Beethoven in the “Hammerklavier” Sonata. The work was so difficult that it remained unperformed in public following its publication in 1819 until the young Franz Liszt showed the way seventeen years later at Paris’s Salle Érard. Pollini describes it as the “greatest Beethoven sonata”. Its slow movement alone is almost as long as all four movements of its companion piece on the album. “You can think also of the funeral march of the ‘Eroica’ Symphony – these are perhaps the two greatest movements Beethoven ever composed,” suggests the pianist. The transition into the fourth and final movement’s fugue, a sublime Largo, dissolves ordinary perceptions of time and space, as if opening the door to an otherwise inaccessible spiritual dimension. It prepares the way for a three-voice fugue sustained and developed over a sequence of contrasting episodes that combine to lift the music out of its historic context and leave it sounding fresh for all time.

“Sometimes Beethoven is considered to have returned to the spirit of older music in his late works, but this is completely wrong,” concludes Pollini. “He uses old techniques to renew his music.”