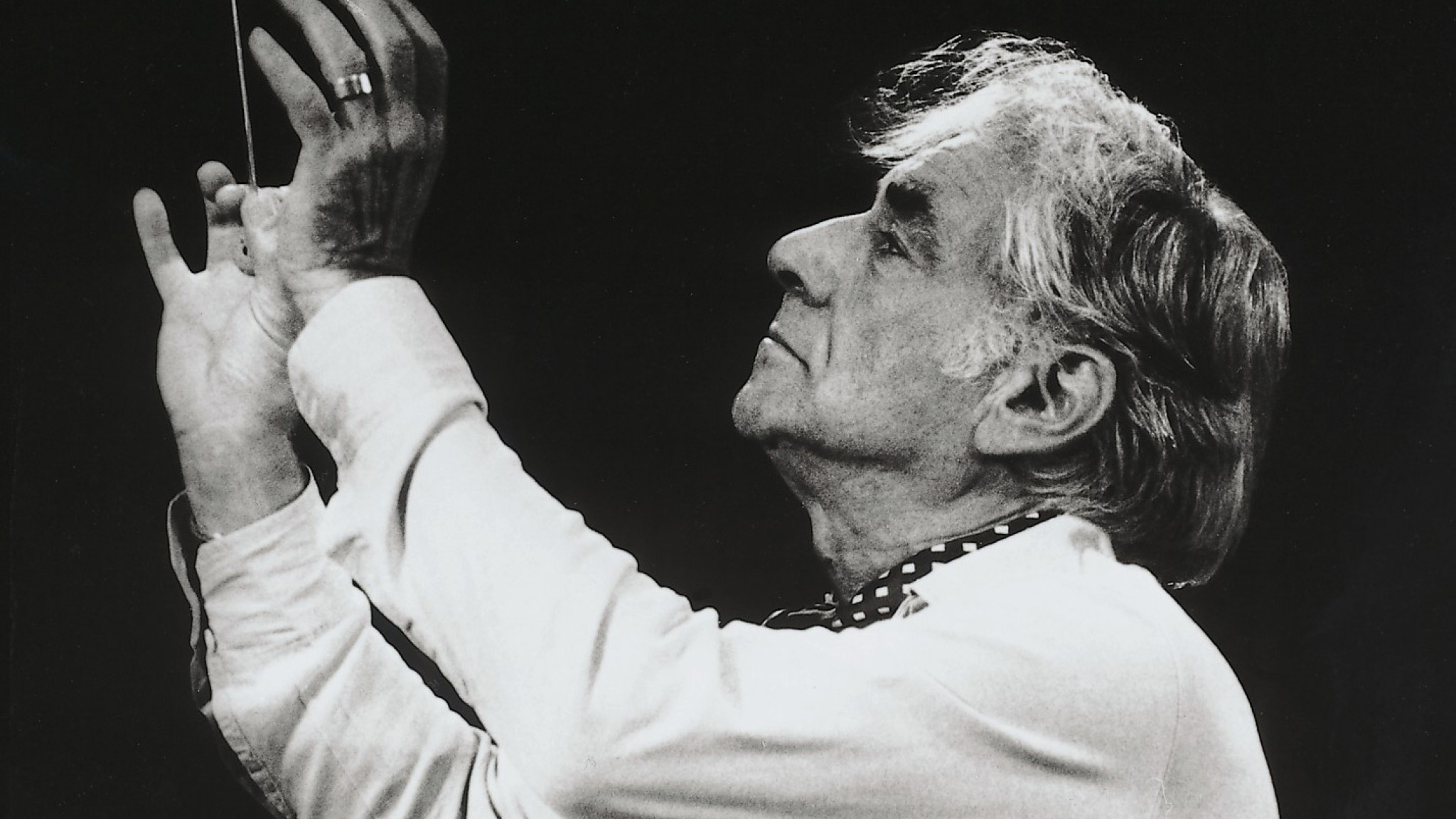

Biography

Leonard Bernstein was a phenomenon. He was the first superstar conductor to have been born in the USA, a gifted pianist, a fiercely intelligent broadcaster and writer, and an inspiring teacher. On top of all that, he was a composer who wrote successful works both for the concert hall and for Broadway. Add in his complex private life and reckless appetites and it’s small wonder that at one point he famously described himself as ‘over-committed on all fronts’. Bernstein was born into a Massachusetts family of Russian Jewish origin, and studied at Harvard University and at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. He also studied conducting at the Tanglewood summer school with Serge Koussevitzky, later becoming his assistant. His big break came in 1943, standing in at short notice for a New York Philharmonic broadcast concert. Later, in 1958, he became music director of the Philharmonic, the first American-born musician to hold the post. His 11 seasons in the job transformed him into an icon of the city. After he stood down he remained a regular visitor to the orchestra, and was given the title of laureate conductor. Meanwhile, he had established an international career with major orchestras and opera companies all over the world. He forged especially close associations with the Israel Philharmonic, London Symphony and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestras. His worldwide fame was such that, when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, he was the obvious choice to conduct the celebratory performance there of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Bernstein’s wide repertoire centred on the Romantic period but ranged from the Classical era to his own time. He championed many American composers and conducted many of their premieres. He was also well known as an exponent of Sibelius, Nielsen, Shostakovich and, above all, Mahler, who he helped to establish as a major figure. A passionate identification with these composers led to accusations of exaggerated expressiveness and unnecessary histrionics on the podium. However, it ensured that his performances were never routine and often revelatory. His programmes frequently included piano concertos which he directed from the keyboard. He was also an adept piano accompanist of singers. Bernstein was always anxious to reach out to the wider audience beyond the concert hall. Most of his repertoire appeared on disc, much of it in multiple versions. Many of his performances are also preserved in video form. He was a much admired presenter of televised Young People’s Concerts and of studio programmes on a wide range of musical topics. Scripts for these programmes often appeared in print, as did many of his other writings. In the early part of his career, Bernstein taught at Tanglewood and Brandeis University. Later he became a revered and much-loved mentor of young conductors in the USA, Germany and Japan. As a composer, he absorbed a wide range of styles and ideas. Aaron Copland, a lifelong friend, had a strong influence on his music. Bernstein was conservative in his adherence to tonality, though in several works he opposed tonal music with atonal or even 12-note writing to dramatise a conflict of ideas. He had a natural grasp of the idioms of popular music and jazz. This allowed him, as it had Gershwin, to move freely between the concert hall and the musical theatre. He first came to national attention as a composer of Broadway musicals. His three greatest hits are all set in New York: On the Town (1944), Wonderful Town (1953) and, above all, West Side Story (1957). This transferred the tragic rivalries of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet to the Manhattan gang scene. Its score ingeniously binds together hit songs and extended dance numbers with a symphonic logic. He also tried his hand at ‘comic opera’ with Candide (1956), adapted from Voltaire’s book. The work is beset with dramatic and structural problems, but contains some of Bernstein’s finest theatre music. 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, composed for the American bicentennial in 1976, was a downright flop. Bernstein made only one other attempt at full-lengh opera. In 1951 he wrote the entertaining one-acter Trouble in Tahiti, which he expanded 32 years later by surrounding it with new material. The result, called A Quiet Place, was considered by many an unconvincing hybrid. His ballet scores include the jazz-coloured Fancy Free (1944), the Copland-esque Facsimile (1946) and the dramatic Dybbuk (1974). He wrote only one film score, but it was a classic, On the Waterfront (1954). Many of Bernstein’s best known concert works are drawn from his stage music. The Three Dance Episodes from On the Town have enjoyed a independent career in the concert hall, as has the Candide Overture and the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story. Later orchestral music is often patchy and lacking in inspiration. But Bernstein’s mastery of orchestration remains evident in works such as the Divertimento for the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1980) and the Concerto for Orchestra for the Israel Philharmonic (1989). His finest work in concerto format is the Serenade (after Plato’s Symposium) for violin and chamber orchestra (1954). This ‘series of related statements in praise of love’ often reaches moments of transcendent radiance. Some of Bernstein’s most successful concert pieces include voices. His choral Chichester Psalms (1965) is based largely on material discarded from West Side Story and other projected musicals. The cantata Songfest (1977) is based on an anthology of American poetry. A rare example of his writing on a chamber scale is Arias and Barcarolles (1988) for two singers and piano duet. Three symphonies form the backbone of Bernstein’s concert output. The First, Jeremiah (1942), ends with a setting for mezzo-soprano of a Hebrew text from the Book of Lamentations. The Second, The Age of Anxiety (1949), recruits a solo piano in its elaboration of a poem by WH Auden. The Third, Kaddish (1963), sets the Hebrew prayer for soprano and two choruses, and also includes a narrator in anguished dialogue with his God. Bernstein described all three symphonies as facets of ‘the work I have been writing all my life… about the struggle that is born of the crisis of our century, a crisis of faith’. This struggle, essentially a personal one, was continued in Mass (1971), ‘a theatre piece for singers, players and dancers’. This is a dramatisation of the Catholic Mass in which the celebrant undergoes a breakdown on the way to enlightenment. Initially criticised as incoherent and irreverent, Mass is now recognised as classic Bernstein in its audacious boundary-crossing and musical eclecticism. The work’s abundant invention, uninhibited idealism and its urgent desire to communicate to the widest possible audience make it the perfect illustration of Bernstein’s artistic aims.